Idaho State Troopers work security Jan. 6, 2020, during the State of the State address at the Idaho Capitol in downtown Boise.

Gov. Brad Little presents the Idaho Teacher of the Year Award to Stacie Lawler in January 2020 during State of the State Address at the Capitol in downtown Boise.

Idaho Speaker of the House Scott Bedke, R-Oakley, left, talks Aug. 24, 2020, with a spectator about social-distancing protocols before the opening of the special session. The gallery had been arranged for socially distanced seating, which was quickly filled and angered the crowd. A glass door to the fourth-floor viewing area was broken, and the crowd chanted ‘Let us in’ before the session. Bedke arranged that protesters could fill the gallery without social distancing if they followed decorum.

Boise Police in riot gear responded Aug. 25 to the Idaho Statehouse to assist Idaho State Troopers as they arrested Ammon Bundy inside the Capitol for refusing to leave a meeting. A mass of protestors, refusing to wear masks and adhere to social distancing rules during the coronavirus pandemic, have demanded to attend the special session of the Idaho Legislature called by Gov. Brad Little.

Spectators in the gallery silently indicate their approval Aug. 25 for speakers who supported a resolution as the House debated a concurrent resolution that would end the coronavirus emergency declaration that Gov. Brad Little signed in March. The House resolution passed 48-20.

State lawmakers are preparing for the 2021 legislative session more than four months after angry spectators shattered a glass door inside the Idaho Capitol to get into a special session where seating was limited.

The Idaho Legislature is hoping for fewer disturbances in the upcoming session.

The Idaho House of Representatives met in August to address the growing COVID-19 pandemic. The unmasked crowd, after growing frustrated with the state’s response to the pandemic, broke through the glass and entered the gallery. One person carried an assault-style weapon.

“We had some unruly people during the special session,” Rep. Sally Toone, a Democrat from Gooding, said. “Their whole goal was to be disruptive and that concerns me. We have a job to do. Let’s do our job.”

Ammon Bundy was among those who pushed their way into the House chambers on Aug. 24. ‘We ended up having to push our way in; eventually they yielded to the people’s voice and they allowed us in, after some pushing and shoving and some shouting,’ he said later. ‘That’s sometimes the way democracy if you want to call it that, is.’

Meanwhile, other legislators think it’s a mistake to begin the session on Monday. And some lawmakers have pushed for changes to the session.

Reps. Sue Chew, D-Boise, and Muffy Davis, D-Ketchum, filed a lawsuit Thursday against the Idaho Legislature and Speaker of the House Scott Bedke seeking the ability to participate in the session remotely.

Rep. Muffy Davis (D-Ketchum) smiles Jan. 6, 2020, during the State of the State address at the Idaho Capitol in downtown Boise.

The complaint states the representatives could “sustain irreparable injury and loss” if they are exposed to COVID-19 during the session because of their existing health issues. According to the complaint, Chew has diabetes and hypertension, while Davis is a paraplegic whose spine injury has compromised her lung function.

Nonetheless, the session is moving forward with some COVID-specific safety precautions in place. This includes limiting the number of people allowed in committee rooms to allow for social distancing. If members of the public can’t testify in person, some committees will allow them to do so remotely, but that decision will be up to the chairperson of each committee.

The Idaho State Police is also urging visitors to wear masks inside the building.

Sen. Lee Heider, R-Twin Falls, said he’s hopeful lawmakers are able to make it through a productive, three-month session, but he’s concerned about the possibility of it getting cut short if there’s an outbreak within the House or Senate.

“I think we’ll be proactive about wearing masks and creating separation,” Heider said. “But we’re also in the same building at the same time, so we’re going to have close contact sometimes.”

Joy Thomas, chief of staff for the minority Democratic party, wipes down desks in March in the Idaho House of Representatives at the Statehouse in Boise .

In December, Senate Minority Leader Michelle Stennett and House Minority Leader Ilana Rubel, a Boise Democrat, wrote a letter urging Bedke and President Pro Tempore Chuck Winder, R-Boise, to support postponing the session until vaccines are more widely available.

Their request was denied.

Idaho Senate Minority Leader Michelle Stennett, D-Ketchum, talks to reporters Jan. 3, 2020, at the Idaho Capitol in Boise.

“I can’t convince them to postpone or go remote,” said Stennett, a Democrat from Ketchum. “So we will go forward with trying to do the best work we can.”

In addition to these logistics, issues surrounding the new coronavirus will factor into bills that legislators write during the session. For example, some lawmakers plan to pursue legislation that would give the legislative branch more power during emergency situations, such as a pandemic.

Ongoing statewide and local issues, such as property tax relief, education funding and agricultural conflicts, are likely to be addressed throughout the session. But it’s too soon to say what specific pieces of legislation will move forward or how long lawmakers will have to pass these bills.

“I would hesitate to guess how this session goes,” Heider said. “This is certainly one that has thrown everybody a real curve. We don’t want anybody to die because we’ve pressed an issue or been stubborn about something.”

Balancing the branches

Like every session, the most important piece of legislation to be passed in the upcoming session is the appropriations bill that funds the state’s various departments. But aside from approving the state’s budget, Bedke said his top priority this session is passing legislation aimed at reining in some of the governor’s powers.

Idaho Gov. Brad Little talks to reporters Jan. 3, 2020, at the Idaho Capitol in Boise.

“Behind (the budget) is resetting the balance of powers between the legislative and executive branch,” he said. “We feel there were prerogatives taken in the early part of the year that should not have happened.”

Bedke said that as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded throughout the year, Gov. Brad Little made decisions that he believes the legislature should have been involved in making.

As an example, Bedke said lawmakers should have had more of a say in how the state used the nearly $1.5 billion it received from the federal government in Cares Act Funding. Additionally, he said that the governor shouldn’t have the ability to continue extending emergency declarations multiple times without input from the legislature. Declaring an emergency opens up other state statutes and allows the governor to make some decisions unilaterally.

“I’m not going to second guess his decisions, but that process ought to be a product of a checks-and-balance system,” Bedke said. “These decisions have a major way of affecting Idahoans, and citizens want their locally elected officials in the middle of those decisions.”

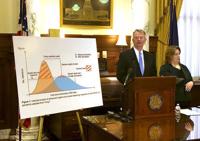

Idaho Gov. Brad Little speaks at a news conference March 13 in Boise and proclaims a state of emergency in Idaho in hopes of preventing the spread of the new coronavirus.

Legislation aimed at addressing this issue could focus on giving the legislature the ability to call itself into a special session. Under state law, the legislature meets once a year for three months, unless the governor extends the session for a specific purpose. If lawmakers have the ability to call themselves back to Boise, this could give them the opportunity to weigh in on decisions during emergencies or other pressing issues.

Because the current process is outlined in the Idaho Constitution, giving the legislature this power would likely require a constitutional amendment that Idahoans would vote on. Bedke said if a bill passes the legislature this year, the amendment will likely be on the ballot in November 2022.

Stennett says giving the legislature the ability to call itself back into session under tight guidelines could be appropriate, depending on the exact bill and how it’s written.

She could potentially support legislation that gives lawmakers the ability to call themselves back into session when the state receives significant funding above a certain dollar amount, such as the $1.5 billion it received in 2020, she said.

One of the benefits of the governor responding to emergencies is that he’s able to be nimble and act quickly, Stennett said. She’s worried that the legislature, given the number of people that are part of the body, wouldn’t be able to respond to emergencies in the same timely manner, which could be a problem during an emergency.

“Would it be more efficient for the legislature to get involved?” Stennett said. “I think some of this would be good for discussion, as long as people aren’t grandstanding.”

The Idaho Statehouse is seen March 4 in Boise. Legislators will begin the 2021 session Monday.

Funding education

With more than 60% of the state’s general fund going toward education expenses, how the state funds its schools is always a discussion during the legislative session.

House Education Committee Chairman Lance Clow said he’d like to see the legislature move forward with legislation that creates a school choice program.

Support Local Journalism

Your membership makes our reporting possible.

{{featured_button_text}}

In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on a case called Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue that essentially allows states to allocate tax revenue to private, religious schools. The court ruled that specific state laws that prohibit government funds from supporting religious schools, often referred to as Blaine Amendments, are unconstitutional, said Clow, a Republican from Twin Falls.

Rep. Lance Clow (R) listens to procedure before the State of the State address Monday afternoon, Jan. 6, 2020, at the state Capitol building in downtown Boise.

With this ruling in place, he said he expects the committee he chairs to work on legislation that creates a program to assist students who choose to opt out of the public school system to enroll in a private school. He referred to the program as an education savings account.

“Take a dollar amount that goes to each public school student and you would set aside a percentage of that, maybe 70% of what would go to a public school student, that a parent could use specifically on approved expenses for the education of their child,” Clow told the Times-News.

The program would have some restrictions in place to determine who is eligible, such as a requirement that families who receive the funding have an income level at a certain percentage below the poverty line. Also, the program could require that the student who is applying previously attended a public school, that way the funding is following the student rather than just being removed from the public school system.

The Idaho Constitution requires the legislature to establish a “uniform and thorough system of public, free common schools.” Stennett said she doesn’t see how the legislature could meet this constitutional responsibility with this sort of school choice program in place.

“They’re saying they’re going to make sure the money will follow the students,” Stennett said. “(The program) would crush our public school systems. We have a constitutional mandate to give free education to our children.”

Instead of this sort of program, the legislature should work to make school funding more equitable throughout the state, she said. More than 90 of the 115 districts in the state rely on supplemental levies that require voter approval to make ends meet. If voters reject the levies, districts have no way to fill in the gaps.

Freshman Rep. Sally Toone, D-Gooding, On Friday at her desk in the Idaho House in Boise.

In recent years, the legislature has discussed switching from an attendance-based funding formula to one that allocates funding based on student enrollment numbers. This seemingly simple shift would make a difference as districts would receive funding based on how many students are enrolled — including those online — rather than the average number of students who physically show up each day.

Toone, a former educator, is in favor of the switch. She said the state was on the right track when it began discussing this change a few years ago, but the talks fell apart over some disagreements that she thinks can be worked out. Toone said she expects this conversation to come up again this session.

In August, the Idaho State Board of Education approved a rule that temporarily allows districts to use an enrollment-based funding formula as many students started attending classes remotely due to COVID-19. Toone said this rule expires at the end of the legislative session, so it’ll be up to legislators whether to extend the measure.

Taxing debate

Tax relief is one of the few topics perhaps more ubiquitous than education during the legislative session.

In some parts of the state, property values are increasing at high rates, leading people to pay more in property taxes even if their local tax rates remain the same. Toone said legislators have looked at ways to address this issue for two years in a row, but haven’t come up with a solution.

Toone would like to see the state homeowner’s exemption cap increased. The exemption currently covers up to $100,000 or 50% of a home’s market value, whichever is less. That means that a $250,000 home with an exemption in place has a taxable value of $150,000.

Other legislators agree that property tax relief is an issue they need to address, but Clow said many of the proposals he’s heard of are unfair to local governments. This includes a proposal to limit the reserves that cities and counties can carry over from one year to another. Local governments often use these funds for large expenses or in emergencies when revenues dry up.

Stennett also said the property tax relief proposals she’s aware of hold local governments responsible for this issue while ignoring changes the state could make. For example, she’s in favor of increasing development impact fees that people have to pay for water, sewer, roads or other infrastructure. This could open up more funds for local governments and decrease their reliance on property taxes.

Multiple local legislators said they’d like to see the state take a different approach to how it handles its internet sales tax revenue.

In 2019, the legislature passed a law that created a fund where all internet sales tax is diverted. Clow said this revenue is supposed to be set aside for five years, but he thinks the state should treat that money the same way it does other sales taxes and give 11.5% of it to cities and counties.

“I think the solution to property tax is to share more of the revenues of the state with the direct understanding that it will reduce property taxes,” he said.

Republican Representative Clark Kauffman applauds during the State of the State address Monday afternoon at the state Capitol building in downtown Boise.

Rep. Clark Kauffman, R-Filer, voted in favor of creating the relief fund in 2019 so that the state could begin collecting this tax.

But now after a few years, Kauffman said he agrees that it’s time the legislature starts using the money for its stated purpose: relieving taxes.

Local priorities

Local legislators plan to tackle subjects of significance in the Magic Valley, aside from the statewide issues.

Heider, who serves on the Resources and Environment Committee, said he wants to address elk depredation issues that have caused hunters strife in recent years.

Elk are technically the property of the state and, because of that, the state reimburses farmers when the animals destroy their crops. The amount the state has paid out in these expenses has increased in recent years with more elk damaging private property in the magic valley, Heider said.

With the problem getting worse, the Idaho Department of Fish and Game tried a new approach in the summer of 2019. Officials with the department shot and killed more than 206 elk as part of an effort to study methods of stopping elk from damaging crops. Hunters were upset by the department’s action, saying that they should have allowed the hunters to shoot the animals instead.

Heider said he’s working on legislation that will hopefully address some of this tension. Instead of financially reimbursing farmers for the crops they lose, the state would provide farmers with fencing material worth the same dollar amount of their loss. The farmer would then install the fence in hopes that it keeps the elk away from their crops. The bill could also allow hunters to hunt elk on private property as long as they have the landowners’ permission.

A cow elk grazes at dawn in Blaine County. Idaho Fish and Game says it’s offering more depredation hunts this year so that sportsmen can help the department keep elk from damaging crops.

“This is a real balancing act to try to keep hunters, farmers, and Fish and Game on an even keel,” Heider said.

Local water issues will also be a focal point during this session, Kauffman said. He anticipates the legislature will try to continue building off of its 2016 effort to replenish the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer, which had reached its lowest point since 1912 before the state began its recharge efforts.

Kauffman said this year he expects the legislature to approve funding to identify additional recharge sites, where water is diverted and then allowed to sink into the giant aquifer.

Idaho Rep. Laura Lickley checks out the different types of insulation in an attic during a South Central Community Action Partnership energy awareness event Thursday, Oct. 10, 2019, at the Glenhaven Home in Twin Falls.

Rep. Laurie Lickley also views water issues as one of her top priorities this session. But in addition to ensuring the state is continuing its efforts to monitor and recharge the aquifer, she said the legislature needs to focus on water quality this session.

“We’ve done a good job on water quantity, but we need to address water quality as well,” said Lickley, a Republican from Jerome. “That’s something that has been talked about over the last several years, but there’s been no targeted projects, and so that’s what we will be doing in this session.”

She also wants to see money dedicated this session to address some of the infrastructure needs of the Magic Valley and elsewhere in the state. Idaho is responsible for 900 bridges with a poor rating — meaning they’re safe to drive on but need improvement.

With these and many other issues to address this session, Lickley says she’s ready for it to start, even though it will look a bit different this year.

“I will be in my seat on Jan. 11 and I will be masked up.”

Subscribe to our Daily Headlines newsletter.